You are here

Boards Get More Independent, but Ties Endure

Outside directors have connections to companies and executives they oversee

First in a series about corporate boards. Also see the interactive graphic I helped create, allowing readers to explore corporate board data.

Shareholders like their corporate boards stocked with independent directors—men and women unencumbered by close ties to the company or its executives. The reasoning: Who better to act in the interest of investors?

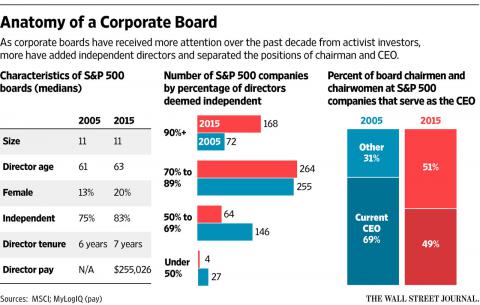

Today, most large companies can boast that their boards are overwhelmingly independent under rules laid down by the stock exchanges. Yet some of those independent directors have close ties to the companies and executives they oversee, or to one another.

John Hennessy, president of Stanford University, has served as an independent director of Google and then its new parent company for 12 years. During that time, the company has given Stanford $24.9 million in donations, scholarships and payments for research services and patent licenses.

Andrew McKenna has been an independent director of McDonald’sCorp. for a quarter century and its chairman for 12 years. He was also the longtime chairman of a family-owned paper-goods company and for a time had a stake in a promotional-items maker, firms that sold a combined $71 million of french-fry bags and other goods to McDonald’s over 22 years.

Charles Gifford and Thomas May serve together on the board of Bank of America Corp. Mr. May, deemed independent, once sat on a committee that oversaw Mr. Gifford’s pay as top executive of another bank. Mr. Gifford serves on a committee overseeing Mr. May’s pay for running a utility company.

Some investors also are bothered by boards filled with longtime directors, reasoning that their long involvement with corporate strategy makes them less inclined to challenge top executives. Ten-year board veterans hold 36% of board seats at S&P 500 companies, compared with 33% in 2005, the data show.

Companies often argue that longtime board members contribute valuable insight and institutional memory in chaotic times, and that independence alone is no guarantee directors will do what is best for investors.

Director independence is a relatively new concern for U.S. corporations. When public companies were dominated by a few big shareholders more than a century ago, directors often monitored management on their behalf. As share ownership became more diffuse, few investors had the clout or incentive to win directorships, and boards largely became advisory bodies, often populated with management’s friends and business associates, according to Charles Elson, head of the University of Delaware’s Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance and one of four insurgent candidates to win a board seat in 2014 at Bob Evans Farms Inc. in an activist campaign.

By the 1980s, large institutional investors began to push boards to become better watchdogs, and in 1996 the National Association of Corporate Directors called for a substantial majority of corporate boards to consist of independent directors. In 2003, the Securities and Exchange Commission approved proposals by the New York Stock Exchange and the Nasdaq to make it a listing requirement. Current federal law requires board committees overseeing executive pay or company audits to include only independent directors.

At fast-growing discount airline Allegiant Travel Co., three of the audit committee’s four members have ties to longtime CEO Maurice J. Gallagher Jr. Two have worked for Mr. Gallagher in the past, including audit chairman Linda Marvin, who was Allegiant’s chief financial officer from 2001 to 2007 and worked for Mr. Gallagher at two prior companies.

Robert Goldberg, a lawyer for Allegiant’s board, said that under Nasdaq rules, Ms. Marvin can be considered independent because she left Allegiant’s executive suite eight years ago. “It is only logical for a CEO to reach out to talented, experienced individuals with whom he has previously worked to advise him as directors in later ventures,” he said.

Among the audit committee’s jobs: approving about $9.3 million in transactions in 2014 between Allegiant and firms controlled or partly owned by Mr. Gallagher, according to Allegiant’s securities filings. That included $3.15 million in rent paid to a firm in which Mr. Gallagher and an audit-committee member are partners. A combined $5.3 million went to advertising with a stock-car racing team Mr. Gallagher owns and to a television-production company, 25% owned by Mr. Gallagher, that filmed game shows aboard Allegiant aircraft, the filings said.

In its 2015 proxy statement, the company called the real-estate and game-show transactions at least as favorable as could have been obtained at arm’s length, and said the publicity value of the racing sponsorship exceeded the cost. Allegiant later said it would stop funding the shows and racing team.

A company spokeswoman said Allegiant acts transparently and is well served by its directors and officers. Over the past five years, Allegiant’s total return to stockholders has been more than double that of the airline industry, according to Morningstar Inc.

Mr. Goldberg, the board lawyer, said Mr. Gallagher and the audit-committee director are minority partners in the firm holding Allegiant’s leases, don’t run it and don’t expect to collect further distributions from it because it has sought bankruptcy protection.

New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq rules about director independence specify who explicitly can’t be designated as such, but companies are supposed to go further. “Then the board has to ask, ‘Are there factors that might cause you to conclude that this director is not independent?’ ” said Edward Knight, general counsel of Nasdaq.

Where two companies do business, an executive at one can qualify as an independent director of the other if the value of annual transactions between the two falls below 2% of gross revenue for NYSE companies or 5% for Nasdaq companies—thresholds that can easily surpass $100 million a year at large companies.

Carnival Corp. director Randall J. Weisenburger qualified as independent while working as chief financial officer for advertising firm Omnicom Group Inc. The cruise operator spent more than $34 million on Omnicom advertising and marketing services during the five years Mr. Weisenburger held both positions, ending in 2014.

A Carnival spokesman said Mr. Weisenburger had no role in overseeing the cruise line’s marketing spending, which he said wasn’t material to either company. In securities filings, Carnival said the transactions totaled a fraction of 1% of Omnicom’s revenue each year. Omnicom declined to comment.

Mr. Hennessy, the Stanford president, became lead independent director of Google’s new parent company, Alphabet Inc., when it was created last year, continuing the role he had at Google.

Google paid about $2.3 million to the university in 2014, mostly for donations or scholarships, and between $546,486 and $7.7 million a year over the previous eight years.

Proxy advisers Glass, Lewis & Co. and Institutional Shareholder Services Inc. have criticized the relationship and recommended that stockholders vote against Mr. Hennessy’s re-election last year. Four of Google’s 10 biggest institutional investors did, according to an analysis by Proxy Insight Ltd. Mr. Hennessey was re-elected.

“President Hennessy recuses himself from any Stanford activity related to Google,” Stanford’s spokeswoman said. Google, which has outperformed other Internet and information-technology companies over the past decade, declined to comment.

Although companies often characterize ties among directors and executives as minor, a Delaware Supreme Court decision in October concluded that small connections can add up. Chief Justice Leo Strine found that several relationships between a director of a public company and a major shareholder were, together, enough to call into question the director’s independence.

Multiple settings

Corporate directors, especially those at big companies, often encounter one another in multiple settings. Such outside ties have the potential to give directors influence over one another.

At Bank of America, the ties between the company’s two longest-serving directors reach back years. Mr. Gifford has served on the board compensation committee at Eversource Energy and a predecessor utility company since 2008, and as the committee’s independent chairman since 2012. In those capacities, he has overseen pay for his Bank of America board colleague, Mr. May, who has been chief executive of Eversource or its predecessor since the 1990s.

Near the beginning of Mr. Gifford’s tenure on the board of the Eversource predecessor company, the roles were reversed. For several years in the early 2000s, Mr. May served on the compensation committee of FleetBoston before the bank’s acquisition by Bank of America. That committee oversaw Mr. Gifford’s compensation as FleetBoston’s chief operating officer and then chief executive.

In addition, since 2010, Mr. May has been chairman of Bank of America’s governance committee. One duty of that committee: recommending which directors should be renominated.

Eversource General Counsel Gregory Butler has said the company fully complies with NYSE listing standards for board and committee independence. Bank of America, whose profits and revenue growth have lagged behind its closest competitors since the financial crisis, declined to comment.

McDonald’s shares have underperformed restaurant companies overall over the past 15 years as the fast-food company has struggled with customer-service complaints and competition from newer chains.

The composition of McDonald’s board came under criticism last year from CtW Investment Group, an arm of labor federation Change to Win that advises union pension funds about the companies they hold stock in. “McDonald’s board appears drawn almost entirely from local or personal networks,” CtW said in a letter to board officials on behalf of unions now holding about 1.8 million shares. “Such a level of insularity and regional bias suggests that the current recruitment process is casting its net far too narrowly, especially for a company of McDonald’s global reach.”

Ten of the company’s 14 directors had significant ties to the Chicago business community, and 10 had served at least a decade, the letter said. CtW also questioned whether Mr. McKenna, the chairman, was sufficiently objective after more than a decade in the position.

McDonald’s filings show that Mr. McKenna served for two decades as chairman of a family-owned paper-goods company, and for a time owned a stake in a promotional-items maker. A McDonald’s spokeswoman said the two firms had done $71 million in business with McDonald’s over 22 years.

In an interview, Mr. McKenna said he is now chairman emeritus of Schwarz Paper, which was sold to a British company in 2012. McDonald’s purchases were a tiny part of Schwartz’s overall revenue over many years, he said, so the relationship “doesn’t even come close to even matter in terms of a challenge to independence.”

Miles White, chairman of the McDonald’s governance committee and CEO of Abbott Laboratories, says the restaurant company’s directors are willing to challenge one another and management despite social ties and long tenure. He noted the McDonald’s board recently replaced the company’s chief executive.

“This is not a go-along, get-along board,” Mr. White said. A board’s independence “has to be measured by its actions.” The two latest McDonald’s directors, announced last August, have no other connections to Chicago.

Dieter Waizenegger, head of CtW’s investment arm, said the company’s corporate-governance changes aren’t enough. ”Given how stagnant this board became, and the scale of the turnaround the company needs to achieve,” he said, “there remains a great deal to be done.”

Mr. McKenna joined the McDonald’s board in 1991, has helped choose five CEOs and has collected about $8.8 million since 2006 for serving as a director. He turned 86 in September. He declined to say how much longer he hopes to lead the board, which doesn’t have a mandatory retirement age.

Write to Theo Francis at theo.francis@wsj.com and Joann S. Lublin at joann.lublin@wsj.com