You are here

Businesses Push Workers to Mobilize Before Tax Revamp

Companies and trade groups turn their tax wish-lists into talking points as federal tax overhaul looms

Part of my contribution to the WSJ's coverage of the 2017 GOP federal tax overhaul legislation.

OMAHA, Neb.—In the parking lot outside Elliott Equipment Co.’s manufacturing plant here last month, more than a hundred employees gathered in front of a banner-bedecked truck, its raised boom flying an American flag 30 feet overhead, to hear from the company’s chief executive and the local congressman.

As Congress and the White House move this week to overhaul the federal tax code, companies of all sizes are preparing for what will likely be the most consequential business lobbying effort in years. In the process, they are mobilizing one of their most potent tools—their employees.

At rallies, in emails and on customized websites, employers and trade groups are turning their tax wish-lists into talking points, making the case that employees should support their employers on such topics as pass-through taxation and deductions for depreciation, interest payments and research. They are collecting employee contact information and fine-tuning online engines that generate form letters to lawmakers.

“Lobbyists have only a certain amount of juice—the people who really have juice are the people who live in the districts,” said a spokesman for the RATE Coalition, a group lobbying for tax-code changes that is composed of large companies and trade groups, including health insurer Aetna Inc., car maker Ford Motor Co. , and telecom giant Verizon Communications Inc. “This is how lobbying is done these days.”

The push also underscores the influence the business community can still wield in Washington, even as its relationship with the White House has frayed. This summer, the administration eliminated several corporate advisory boards after some executives broke publicly with President Donald Trump over issues of race, immigration, climate change and more.

Yet employers still have powerful allies on Capitol Hill, and transforming their workforces into a coordinated lobbying corps has the potential to increase their clout there.

Unions have long talked politics with their members, and many large companies have political-action committees to solicit donations from top managers and other senior employees to spend on elections. Increasingly, however, companies are talking to rank-and-file workers about not just corporate taxes but also international trade, environmental regulations, workplace rules and even elections.

Employees at Campbell Soup Co. , based in Camden, N.J., sent about 6,400 letters to state lawmakers last fall, part of successful efforts to head off Republican Gov. Chris Christie’s threat to end a state income-tax agreement with neighboring Pennsylvania. Medical supplier Becton, Dickinson & Co. asked workers this year to urge Congress to repeal an existing medical-device tax, and oppose steep cuts to National Institutes of Health funding. The device tax has survived as Republican health-care overhauls have failed, and Congress hasn’t implemented the NIH cuts. Both companies say they will likely mobilize employees on tax overhaul.

“Members of Congress want to hear from their constituents, the people they represent,” said Elizabeth Woody, Becton Dickinson’s vice president of public policy and government relations.

Lawmakers seem just as enthusiastic about workplace whistle-stops. House Speaker Paul Ryan (R., Wis.) has talked tax overhaul at Intel Corp. in Oregon, Boeing Co. in Everett, Wash. and smaller firms in Maryland and Pennsylvania. Kevin Brady, the Texas Republican who heads the House’s powerful budget-writing Ways and Means Committee, went to United Parcel Service Inc. in Louisville, Ky., as well as AT&T Inc. in Dallas.

U.S. Rep. Don Bacon, the freshman Nebraska Republican who visited Elliott Equipment, said he prefers meeting constituents at work because he can hear from business owners and voters directly and see what they do. Plus, he adds, when they ask tough questions at work, they tend to keep their passions in check.

“You’re not getting all the naysayers or all the critics,” said Mr. Bacon, who won his seat last fall after a nearly 30-year Air Force career. “If I could do more of these events, I would.”

Elliott Equipment employees gathered in the company’s Omaha parking lot to hear from the CEO and Rep. Bacon about tax reform and other Washington issues as part of a rally organized by the Association of Equipment Manufacturers under its I Make America project. Photo: Theo Francis/The Wall Street Journal

Family-owned Elliott Equipment and other small firms often take part through trade associations. The Omaha rally was one of about 35 planned this year by I Make America, an employee-lobbying project of the Association of Equipment Manufacturers begun in 2010. This year for the first time, every workplace event features elected officials, after experiments last year proved the approach’s effectiveness.

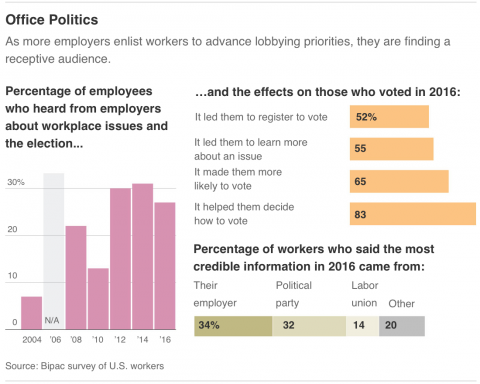

Bipac, a trade group founded in 1963 as the Business-Industry Political Action Committee, provides a suite of software and Washington policy updates, helping AEM and some 300 other companies and trade associations frame issues for employees. That is up from about 50 in 2000, around the time the group made employee mobilization its primary focus.

Beltway organizations better known for traditional advertising and shoe-leather lobbying are also stepping up worker-mobilization efforts. The Business Roundtable, which represents big-company chief executive officers in Washington, is asking its 204 member CEOs to preach the merits of a tax overhaul to their 16 million employees as part of a broader push. As legislation takes shape, they will start encouraging employees to contact lawmakers as well.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, meantime, is urging member companies to send employees to “Tax Reform for America,” a website it runs that immediately invites visitors to write their lawmakers about the urgency of tax overhaul.

“Our companies have been waiting 30 years to get tax done, and part of that is using every single tool they have,” said Abby Majlak, senior director of political affairs for the Chamber. “When [Congress] members see what employees are saying, they’re going to be more likely to support pro-growth tax reform.”

Bipac’s online tools have helped Scott Hawkins, the group’s chairman, organize employees at his group of Alaskan oilfield-services firms, including Associated Service Companies International LLC, as well as a statewide coalition of employers under Bipac’s umbrella. He said 30% to 50% of employees typically respond when asked to contact lawmakers.

Mr. Hawkins knows his 200 or so workers hold varied political opinions, but he was pleased when about 100 of them sent messages to lawmakers on a recent state-tax issue, nearly all backing the company’s position. “We saw about three or four of them were urging the opposite,” he said.

That highlights the concerns critics raise about employee mobilization: What sounds like a request from anyone else can sound a lot less voluntary from the boss. And just the suspicion that the boss is watching who sends a letter, or what they say, could be nearly as effective as outright coercion or threats, argues Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, a Columbia University political scientist whose book on employee mobilization, Politics at Work, is scheduled for publication by Oxford University Press next spring.

“If workers are responding to their managers not because they are genuinely persuaded by corporate political messages, but because they are fearful of losing their jobs,” he writes, “we ought to worry that some workers are being pressured into giving up their political voice to their employers.”

Mr. Hawkins, like other employers and trade groups engaging in employee mobilization, says he doesn’t tell workers how to vote, and doesn’t require participation; nor do dissenting workers face repercussions. Many employers say they don’t track what employees write.

“They can opt out of it by deleting the email,” Mr. Hawkins said. “Just don’t attend the general meeting, just don’t read the email or don’t write the letter.”

Federal law gives employers broad leeway to hold mandatory workplace meetings, including about politics—as long as they don’t threaten or coerce employees, legal experts say. Some states—including California, Montana, Wisconsin and Oregon—have laws imposing some limits on the workplace politicking employers can do, notes Marquette University law professor Paul Secunda.

Elliott Equipment Chief Executive Jim Glazer first mentioned taxes in a conference-room gathering before the rally. Rep. Bacon asked him and his brother John, also a company executive, about their most pressing issues.

Jim Glazer cited taxes, trade, worker training and infrastructure spending, since Elliott’s customers include utilities and state highway departments. He noted the firm is an S corporation, meaning its owners are taxed on business profits, rather than the company itself.

Mr. Bacon said House Republicans had S corporation interests in mind, noting their owners can face marginal federal tax rates close to 44% on business income. “We’re taking corporate down to 20% and S corporations to 25%,” he assured them. “That’s our starting point.”

The Glazers showed Mr. Bacon around Elliott’s 135,000-square-foot facility, where he chatted with company employees as they paused from fitting out boom trucks like those utility companies use to repair power lines.

Then most of the company’s 150 employees gathered outside, many adding their names to I Make America’s mailing list of manufacturing employees—already 40,000 strong—in return for a hat, beer koozie or bottle opener bearing the group’s logo.

As legislation develops in Washington, I Make America will send emails urging members to contact lawmakers on provisions that matter to manufacturers, with easy links to websites that generate and send editable form letters. Mr. Bacon’s predecessor in Nebraska’s Second Congressional District, a Democrat, also met with member-company employees under I Make America’s banner.

I Make America has found that people who sign up at work are almost twice as likely to write lawmakers when asked, compared with those who sign up online or elsewhere, says AEM Vice President, Public Affairs & Advocacy Kip Eideberg, a lobbyist who coordinates many of the rallies.

The events help Mr. Eideberg do his job, too. He and company executives typically get about 90 minutes with elected officials on a factory tour, compared with perhaps 20 or 30 minutes with aides on Capitol Hill.

“In D.C., you rarely see the lawmakers,” Mr. Eideberg said. “We are building really good relationships with members of Congress.”

Mr. Bacon’s speech to Elliott employees piqued the curiosity of Alex Legon, a material handler who has worked at Elliott for about three years. He wasn’t previously familiar with S corporations, or how different companies are taxed, he said. “It makes me want to look into it more.”

—Richard Rubin contributed to this article.