You are here

Companies Tap Pension Plans To Fund Executive Benefits

Little-Known Move Uses Tax Break Meant for Rank and File

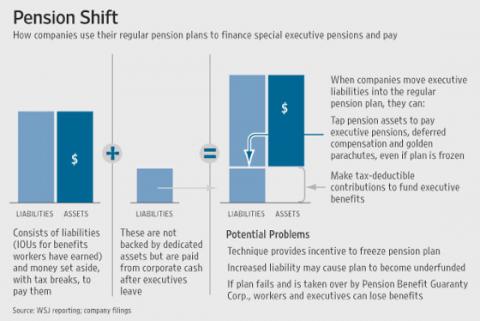

At a time when scores of companies are freezing pensions for their workers, some are quietly converting their pension plans into resources to finance their executives' retirement benefits and pay.

In recent years, companies from Intel Corp. to CenturyTel Inc. collectively have moved hundreds of millions of dollars of obligations for executive benefits into rank-and-file pension plans. This lets companies capture tax breaks intended for pensions of regular workers and use them to pay for executives' supplemental benefits and compensation.

The practice has drawn scant notice. A close examination by The Wall Street Journal shows how it works and reveals that the maneuver, besides being a dubious use of tax law, risks harming regular workers. It can drain assets from pension plans and make them more likely to fail. Now, with the current bear market in stocks weakening many pension plans, this practice could put more in jeopardy.

How many is impossible to tell. Neither the Internal Revenue Service nor other agencies track this maneuver. Employers generally reveal little about it. Some benefits consultants have warned them not to, in order to forestall a backlash by regulators and lower-level workers.

The background: Federal law encourages employers to offer pensions by giving companies a tax deduction when they contribute cash to a pension plan, and by letting the money in the plan grow tax free. Executives, like anyone else, can participate in these plans.

But their benefits can't be disproportionately large. IRS rules say pension plans must not "discriminate in favor of highly compensated employees." If a company wants to give its executives larger pensions -- as most do -- it must provide "supplemental" executive pensions, which don't carry any tax advantages.

The trick is to find a way to move some of the obligations for supplemental pensions into the plan that qualifies for tax breaks. Benefits consultants market sophisticated techniques to help companies do just that, without running afoul of IRS rules against favoring the highly paid.

Intel's case shows how lucrative such a move can be. It involves Intel's obligation to pay deferred compensation to executives when they retire or leave. In 2005, the chip maker moved more than $200 million of its deferred-comp IOUs into its pension plan. Then it contributed at least $187 million of cash to the plan.

Now, when the executives get ready to collect their deferred salaries, Intel won't have to pay them out of cash; the pension plan will pay them.

Normally, companies can deduct the cost of deferred comp only when they actually pay it, often many years after the obligation is incurred. But Intel's contribution to the pension plan was deductible immediately. Its tax saving: $65 million in the first year. In other words, taxpayers helped finance Intel's executive compensation.

Meanwhile, the move is enabling Intel to book as much as an extra $136 million of profit over the 10 years that began in 2005. That reflects the investment return Intel assumes on the $187 million.

Fred Thiele, Intel's global retirement manager, said the benefit was probably somewhat lower, because if Intel hadn't contributed this $187 million to the pension plan, it would have invested the cash or used it in some other productive way.

The company said the move aided shareholders and didn't hurt lower-paid employees because most don't benefit from Intel's pension plan. Instead, they receive their retirement benefits mainly from a profit-sharing plan, with the pension plan serving as a backup in case profit-sharing falls short.

The result, though, is that a majority of the tax-advantaged assets in Intel's pension plan are dedicated not to providing pensions for the rank and file but to paying deferred compensation of the company's most highly paid employees, roughly 4% of the work force.

And taxpayers are on the hook in other ways. When deferred executive salaries and bonuses are part of a pension plan, they can be rolled over into an Individual Retirement Account -- another tax-advantaged vehicle.

Intel believes that its practices "feel consistent" with both the spirit and letter of the law that gives tax benefits for providing pensions.

Intel may be a model for what's to come. Many companies are phasing out their pension plans, typically by "freezing" them, i.e., ending workers' buildup of new benefits. This leaves more pension assets available to cover executives' compensation and supplemental benefits. A number of companies have shifted executive benefits into frozen pension plans.

Technically, a company makes this move by increasing an executive's benefit in the regular pension plan by X dollars and canceling X dollars of the executive's deferred comp or supplemental pension.

CenturyTel, for instance, in 2005 moved its IOU for the supplemental pensions of 18 top employees into its regular pension plan. Chief Executive Glen Post's benefits in the regular pension plan jumped to $110,000 a year from $12,000. A spokesman for the Monroe, La., company, which made more such transfers in 2006, was frank about its motive: to take advantage of tax breaks by paying executive benefits out of a tax-advantaged pension plan.

So how can companies boost regular pension benefits for select executives while still passing the IRS's nondiscrimination tests? Benefits consultants help them figure out how.

To prove they don't discriminate, companies are supposed to compare what low-paid and high-paid employees receive from the pension plan. They don't have to compare actual individuals; they can compare ratios of the benefits received by groups of highly paid vs. groups of lower-paid employees.

Such a measure creates the potential for gerrymandering -- carefully moving employees about, in various theoretical groupings, to achieve a desired outcome.

Another technique: Count Social Security as part of the pension. This effectively raises low-paid employees' overall retirement benefits by a greater percentage than it raises those of the highly paid -- enabling companies to then increase the pensions of higher-paid people.

Indeed, "it is actually these discrimination tests that give rise to Qserp in the first place!" said materials from one consulting firm, Watson Wyatt Worldwide. "Qserp" means "qualified supplemental executive retirement plan" -- an industry term for a supplemental executive pension that "qualifies" for tax breaks.

Watson Wyatt senior consultant Alan Glickstein said the firm's calculations tell employers exactly how much disparity they can achieve between the pensions of highly paid people and others. "At the end, when the game is over, when the computer is cooling off, you know whether you passed [the IRS nondiscrimination tests] or not," he said. At that point, companies can retrofit the benefits of select executives, feeding some into the pension plan.

They can do this even if they freeze the pension plan, because executives' supplemental benefits and deferred comp aren't based on the frozen pension formula.

Generally, only the executives are aware this is being done. Benefits consultants have advised companies to keep quiet to avoid an employee backlash. In material prepared for employers, Robert Schmidt, a consulting actuary with Milliman Inc., said that to "minimize this problem" of employee relations, companies should draw up a memo describing the transfer of supplemental executive benefits to the pension plan and give it "only to employees who are eligible."

The IRS was also a concern for Mr. Schmidt. He advised employers that in "dealing with the IRS," they should ask it for an approval letter, because if the agency later cracks down, its restrictions probably won't be retroactive.

"At some point in the future, the IRS may well take the position" that supplemental executive pensions moved into a regular pension plan "violate the 'spirit' of the nondiscrimination rules," Mr. Schmidt wrote. In an interview, he confirmed his written comments.

Companies don't explicitly tell the IRS that an amendment is intended to shift supplements executive benefits obligations into the regular pension plan. "They hide it," a Treasury official said. "They include the amendment with other amendments, and don't make it obvious."

With too little staffing to check the dozens of pages of actuaries' calculations, the IRS generally accepts the companies' assurances that their pension plans pass the discrimination tests, the official said.

"Under existing rules, there's little we can do anyway. If Congress doesn't like it, it can change the rules." To halt the practice, Congress would have to end the flexibility that companies now have in meeting the IRS nondiscrimination tests.

A spokesman for the IRS said it has no idea how many such pension amendments it has approved or how much money is involved.

Sometimes, the only tipoff that a firm is moving executive benefits into the regular pension is that it provides small increases to some lower-paid groups in the plan, in order to pass the nondiscrimination tests.

Royal &SunAlliance, an insurer, sold a division and laid off its 228 employees in 1999. Just before doing so, it amended the division's pension plan to award larger benefits to eight departing officers and directors. One human-resources executive got an additional $5,270 a month for life.

But to do this and still pass the IRS's nondiscrimination tests, the company needed to give tiny pension increases to 100 lower-level workers, said the company's benefits consultant, PricewaterhouseCoopers. One got an increase of $1.92 a month.

Joseph Gromala, a middle manager who stood to get $8.87 more a month at age 65, wrote to the company seeking details about higher sums other people were receiving. A lawyer wrote back saying the company didn't have to show him the relevant pension-plan amendment.

Mr. Gromala then sued in federal court, claiming that administrators of the pension plan were breaching their duty to operate it in participants' best interests. The company replied that its move was a business decision, not a pension decision, so the fiduciary issue was moot. The Sixth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed.

PricewaterhouseCoopers declined to comment. A spokesman for Royal &SunAlliance's former U.S. operation, now called Arrowpoint Capital, said the pension plan "wasn't discriminatory." Royal &SunAlliance recently changed its name to RSA Insurance Group.

Pension-plan amendments like the documents Mr. Gromala sought must be filed with the IRS, but the agency normally won't disclose specifics such as who benefits. The IRS says it can't release details of the amendments because they reflect individuals' benefits.

Employers sometimes tell executives that moving their supplemental pensions or deferred comp into the company pension plan will make them more secure. Normally, supplemental pensions or deferred comp are just unsecured promises; companies don't set aside cash for supplemental executive pensions and deferred comp because there's no tax break for doing so. But the promises will be backed by assets if the company can squeeze them into a tax-advantaged pension plan.

This supposed security can prove illusory, as executives at Consolidated Freightways found out.

The trucking firm moved most of its retirement IOUs for eight top officers into its pension plan in late 2001. It said this would protect most or all of their promised benefits, which ranged up to $139,000 a year.

This came as relief to Tom Paulsen, then chief operating officer, who says he knew the Vancouver, Wash., trucking company was on "thin ice."

But the pension plan was underfunded. And Consolidated didn't add more assets to it when the company gave the plan new obligations. Adding the executive IOUs thus made the plan weaker. It went from having about 96% of the assets needed to pay promised benefits to having just 79%.

Consolidated later filed for bankruptcy and handed its pension plan over to a government insurer, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. The PBGC commits to paying pensions only up to certain limits. Mr. Paulsen said he and other executives have been told they won't get their supplemental pensions.

Some lower-level people will lose benefits, too. Chester Madison, a middle manager who retired in 2002 after 33 years, saw his pension fall to $20,400 a year from $49,200. Mr. Madison, 62, has taken a job selling flooring in Sacramento, Calif.

He faults those who made the pension decisions. "I look at it as greed and taking care of the top echelons," he says.

It's impossible to know how much the addition of executive pensions to the pension plan contributed to the plan's failure. But in this as in similar companies where a plan saddled with executive benefits failed -- such as at kitchenware maker Oneida Ltd. in upstate New York -- it's clear the move weakened the plans by adding liabilities but no assets.

A trustee for Consolidated's bankruptcy liquidation declined to discuss details of the company's pension plan.

Mr. Madison and five other ex-employees sued Towers Perrin, a consulting firm that had advised Consolidated on structuring its benefits. The suit, alleging professional negligence over this and other issues, was dismissed in late 2006 by a federal court in the Northern District of California. Towers Perrin declined to comment.

Some companies, after moving executives' supplemental benefits into a pension plan, now take steps to protect them. When Hartmarx Corp. added executive obligations to its pension plan last year, it set up a trust that automatically would be funded if the plan failed.

Glenn Morgan, the clothier's chief financial officer, said the trust benefits nine or 10 people. "The purpose is to pay them the benefit they've earned," he said.

(See related letters: "The Captains Commandeer the Pension Lifeboats" -- WSJ August 12, 2008)