You are here

Study Points to Windfall for Goldman Partners

The New York Times ran the following piece (and a video) delving into the secretive tier of elite partners at Goldman Sachs, based largely on my work at Footnoted.

Goldman Sachs executives have long been among the most richly paid on Wall Street in the best of times. They are now poised to reap a windfall that was sown in the dark days of the financial crisis in 2008.

Nearly 36 million stock options were granted to employees in December 2008 — 10 times the amount issued the previous year — when the stock was trading at $78.78. Since those uncertain days, Goldman’s business has roared back and its share price has more than doubled, closing on Tuesday at nearly $175.

The options grant is among the many details that emerge from a study of regulatory filings and internal partnership documents by The New York Times andFootnoted.com, a division of Morningstar that scrutinizes corporate disclosures. These filings provide a much fuller picture of both Goldman’s compensation and its elite partnership of 475 people who run the firm.

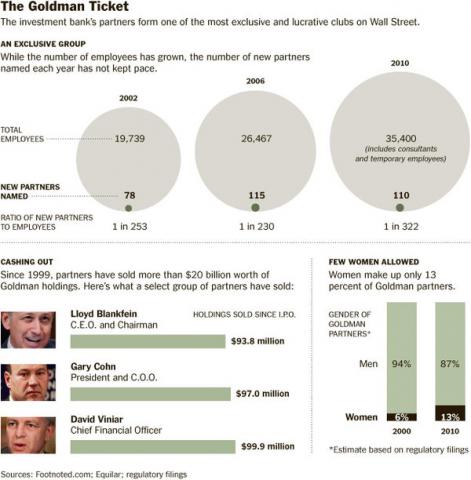

The documents illustrate just how much wealth the partnership owns and has cashed out over the years. Goldman has almost 860 current and former partners, the documents show. In the last 12 years, they have cashed out more than $20 billion in Goldman shares and currently hold more than $10 billion in Goldman stock.

All Wall Street firms dole out stock to reward their employees. But the reporting of who gets what and who sells is typically limited to the firm’s top officers. The Goldman filings provide a window into how broad and how lucrative stock-based compensation can be.

The 2008 stock option grant came at a time when the firm’s financial performance took a hit and its top executives were not paid bonuses. The grant, much of it awarded to partners, gave options that could be exercised in one-third installments in January 2010, January 2011 and January 2012. The shares cannot be sold or transferred until January 2014. The award has already helped increase the partners’ stake in Goldman to 11.2 percent, from 8.7 percent. And as additional options vest, the partners’ control of the firm will most likely increase.

Goldman declined to comment.

In addition to the cumulative stock sales and stock ownership, the filings show an inner circle that is chiefly male — 87 percent of the current partners are men — and shed light on how much each partner has cashed out over the years. The analysis, which examined nearly 5,000 pages of regulatory filings, was a joint effort by The Times and Footnoted.com’s senior reporter Theo Francis.

With Goldman set to report earnings on Wednesday, the newest class of inductees will get their first glimpse into the privileges of partnership, as the firm begins to notify its more than 35,000 employees about their year-end bonuses. Goldman is on track to pay out $17.5 billion in compensation for last year. While that is down from the record $20.19 billion in 2007, it’s up more than a billion from 2009.

The documents also show what shares partners sold before they became officers and were required to make disclosures. Lloyd C. Blankfein, Goldman’s chief executive, for example, has cashed in a total of $93.8 million in shares since 1999, a number that captures both known stock sales since he became an officer at Goldman, and sales not individually reported since before he was required to disclose such transactions.

In the eight years since becoming a senior executive in 2002, Mr. Blankfein has sold $42.5 million, roughly 45 percent of the total over the years. As of August, Mr. Blankfein and his family owned 2.03 million shares worth about $355 million if they had been cashed out on Jan. 14.

Over all for the partnership, the stock sales amount to around $24 million on average for each partner since the 1999 initial public offering — a conservative estimate since the documents do not capture every sale by a Goldman partner, or shares sold as part of the public offering. Pay packages also include cash salaries and bonuses, and this analysis does not include the billions of dollars Goldman has paid in those categories.

Goldman’s stock has returned nearly 175 percent since the close of its May 1999 initial public offering. The Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index over the same period has lost almost 2.9 percent. But the gains of Goldman employees from stock options since the financial collapse have been particularly striking.

In December 2008, just three months after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothersbrought the financial system to the brink, Goldman awarded the nearly 36 million stock options. The number approved by Goldman’s board dwarfed not only the previous year’s grant of 3.5 million options, but also exceed the entire amount of options previously outstanding. The December 2008 options grant was disclosed as required, but received scant attention at the time.

While the partners cannot sell new stock when they exercise the options for another few years, and thus cannot yet lock in their gains, the increased value nonetheless indicates how much they stand to gain when they can.

Because of fierce criticism of Wall Street pay after the financial crisis, most firms have shifted pay practices toward greater stock-based pay — like options and stock grants that cannot be sold for a period, linking the employee’s performance to that of the firm and discouraging reckless risk taking.

But neither Morgan Stanley nor JPMorgan Chase, Goldman’s two biggest rivals, made similar moves to increase sharply the number of options granted while their shares were depressed, according to analysts. And much of Goldman’s options grant went to its partners. Citigroup did issue a number of options during the crisis, but the total issue represented just 1 percent of the shares outstanding, compared with 7 percent at Goldman.

The partnership system is a vestige of Goldman’s days as a private firm. Most Wall Street firms shed their partnerships after going public. But Goldman, one of the last big investment banks to sell shares to the public, created a hybrid model, as an incentive for employees. Goldman releases the names of the new partners, but keeps the full membership list close to the vest.

It’s a formidable group. The members are typically the firm’s most senior executives, including Mr. Blankfein and chief operating officer Gary D. Cohn. Among the alumni are powerful figures in government and finance like former Treasury SecretariesHenry M. Paulson Jr. and Robert E. Rubin, the former governor of New Jersey Jon Corzine, as well as William C. Dudley, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The club is also heavily male. When Goldman went public, only 6 percent of the partners were women, including the senior economist Abby Joseph Cohen. That percentage has risen to a little more than twice that today.

As a group, the partners have considerable sway at the company, not only in the day-to-day operations but also in the long-term vision.

Employees have often been large shareholders at investment banks. What’s different about the Goldman partnership is that they vote as a block, giving them an unusual amount of influence on key decisions at the firm’s annual meetings, from board selection to shareholder proposals on pay. The group casts secret ballots ahead of time to decide their position, according to the filings.

To ensure they maintain a significant stake, the partnership typically asks members to hold on to 25 percent of the shares they receive after joining the group. The figure rises to 75 percent for senior officers. A three-person committee that represents the partnership shareholders (its members are Mr. Blankfein, Mr. Cohn and the chief financial officer, David A. Viniar) can decide to waive the limits for partners in certain circumstances.

The club has gotten even more selective as the company has grown. In 2000, Goldman announced 110 new partners, about 0.5 percent of employees. Last year, Goldman tapped 110 executives, just 0.33 percent of the staff.

The partnership is purged as new blood comes in. Every two years, roughly 70 executives leave the club, by choice or because they are no longer pulling their weight. The average tenure is around seven years.

Of the original class of 221 executives formed after the firm’s I.P.O. in 1999, only 39 remain. Within five years of the I.P.O., almost 60 percent of the original partners were gone. The handful of survivors dominate the top ranks, including Mr. Blankfein, Mr. Cohn and Mr. Viniar.

Most partners who have left, like Mr. Paulson and Mr. Dudley, go on to big jobs elsewhere.

“It is a very Darwinian, survival-of-the-fittest firm,” said one former Goldman partner.

- Log in to post comments